India saw some ground-breaking changes in water policies with a ministry carved out specifically for water, the Jal Shakti Ministry. In the India Water Week 2019, the ministry demonstrated its outreach to other institutions, private and non-profit initiatives as well as research institutes. While confronted with climate change and droughts, floods and their impact on livelihoods and agriculture, the ministry has started very ambitious projects for the upcoming years.

While India is still grappling with the aftermath of this year’s droughts and monsoon floods, another challenge surfaced as it does every year: the issue of water federalism. The question of water-sharing between India’s states is one that is affecting state economies, agriculture, livelihoods and party politics. In his opening remarks, His Excellency German Ambassador Walter Lindner reminded of the global responsibility all countries had pertaining to climate change. It was time for a mindset change and increased cooperation to prevent escalations of climate conflicts. The Honourable Secretary at the aforementioned Jal Shakti Ministry, Shri U. P. Singh, made similar remarks in his Keynote speech: he underlined the ministry’s endeavours on cooperation on all federal levels but also with civil society initiatives and NGOs. Furthermore, Singh pointed out the new attention water was getting from public and government likewise. In a refreshing openness, he spoke about current shortfalls and the government’s plans to overcome these. With a focus on performance and only scientifically proven solutions from, we can expect the Jal Shakti Ministry to take serious steps in order to achieve their ambitious goals.

In the three following thematic sessions, the experts debated on water federalism 2.0, status quo and solutions for the Brahmaputra basin as well as for the Ganga basin.

The session on water federalism brought together practical, legal and academic aspects. Shakti Sinha, director of the NMML and a retired senior IAS bureaucrat argued for a look into existing knowledge and techniques to improve water sharing and consumption. He openly criticised practices uncommon to India such as water-intensive crops that crowded out native ones and were even subsidised. Politics had to set the right incentives there. Professor Balveer Arora and Sh. Siddiqui shed light on the legal and political background of India’s water federalism. A water federalism 2.0 would have to change the jurisdiction over water for a better governance. In India’s current governmental layout, “vertical cooperation has far out-stretched horizontal cooperation” (Arora), with the result of withering away of communication channels vital to the prevention of conflicts over resources. With “states only reacting” (Siddiqui) to conflicts, resource allocation between India’s states remains ineffective, a judicial burden and – as seen in the past years – a source of law & order-situations.

One bill that is soon to be tabled with the Lok Sabha could bring tremendous change in the way, water conflicts are currently solved: The River Basin Management Act. It is supposed to replace the ineffective River Board Act. But the consensus was that more work needed to be done on the draft bill to make it effective and solve water federalism issues of India.

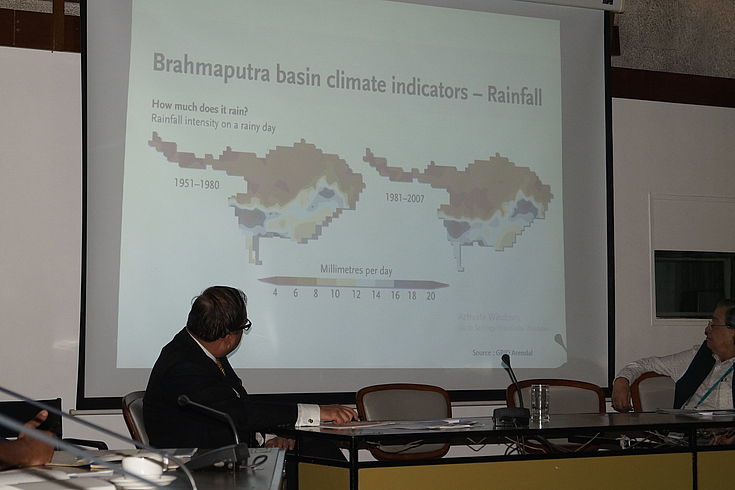

Similarly, in the session on the Brahmaputra basin, the consensus on the dais was that existing structures were not working effectively. “Water cooperation is playing an increasingly important role” as Prof. Chandan Mahanta pointed out. And one that is not only crucial for India’s water security in the Brahmaputra basin, but also transboundary: a “proper water sharing agreement between China and India is required”. Yet currently, even the exchange of data between both countries is not working smoothly. So Prof. Mahanta argued for a “Brahmaputra treaty” similar to the Indus Water Treaty.

High hopes on the upcoming River Basin Management Bill were put on by the experts on the Ganga basin panel. There was a demand for improvement in terms of technical efficiency and training as Ganga treatment plans were lacking capacities and staff expertise. “We should not always look to the courts to give us directions”, as Brijesh Sikka, former Advisor on Rivers to the Minister for Environment, Forests and Climate Change.

Besides the exchange among the speakers and participants from the audience, the conference provided a new look on India’s water federalism. The Foundation and Asian Confluence will continue to pursue the topic “Water Federalism 2.0”; a comprehensive report can be found here shortly.